On Stoicism: Junco Partner

The brilliance of James Booker and the racial politics of the song of the sad junkie

This is a version of a piece that was published in Guernica in 2021. I’ve restored some material that had to be cut and added some images and video of the incandescent Booker. Also of Richard Pryor and Wile E. Coyote.

There once was a prison so shitty that in any given year one out of every ten men confined there could expect to be stabbed. In 1952, thirty-one inmates slashed their Achilles tendons to protest their conditions, which were essentially those of slavery minus the technicality of ownership. The protestors became known as the Heel String Gang. They were in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

One year before the Heel String Gang, James Waynes, also known as James Wayne, recorded a song called “Junco Partner (Worthless Man).” It was written by Bob Shad, though some say Shad was a sham and Waynes wrote it himself or maybe adapted it from one of the hundreds of older tunes that were laid in alluvial deposits in the bottomlands of the Mississippi.

Mac (Dr. John) Rebbenack, who cut his own version of the song in the 1970s, said that it had already been a street anthem in New Orleans, "the anthem of the dopers, the whores, the pimps, the cons.”1

According to Rebennack, the song’s shuffling rhythm was known as “the jailbird beat.” “Junco Partner” would’ve also been known at Angola, and one verse name-checks the prison:

. . . six months ain’t no sentence

. . . one year ain’t no time

They got boys up in Angola

Serving nine to ninety-nine

For all that, “Junco Partner” isn’t really a prison song. It’s a song about the kind of man who often ends up in prison—at least in Louisiana, which currently locks up a greater proportion of its residents than almost every other state in the Union, 1,250 per every 100,000.2 At this writing, more than half of those inmates are Black.3 Most of them are there for drug possession.4

So a song about the “Worthless Man.”

An irony of the song’s subtitle is that the men incarcerated at Angola were hardly worthless. The prison leased them out as farm labor, a practice that began when Angola was a plantation named for the country from which the first generation of its slaves had been kidnaped. While the prison eventually gave up the lease system, it continued to rely on forced labor, but the inmates—who were sometimes called “hands,” in the manner of field slaves—were now paid between four cents and one dollar an hour. When laborers went on strike in 2018, the administration issued a statement: “Agriculture work at the prison provides offenders with a skill they may use once they are released from prison, and the produce helps feed the offenders at the state’s prisons.”5

You could read this conflict as being fundamentally about value. The prisoners argued that their labor had value and ought to be compensated as such. The prison administration agreed about the existence of said value but insisted that the beneficiaries were the prisoners themselves: Their prescribed labor turned worthless men into worthwhile ones. A savvier public affairs office might have called it an internship.

***

Different recordings of “Junco Partner” came out in bursts. Waynes’s was followed a year later by cover versions by Richard Hayes and Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five, who gave it a Latin treatment. After Dr. John covered it in 1972, Professor Longhair took a turn in 1974, and then classically-trained James Booker in 1976: the song passing like a relay’s baton between the three towering virtuosos of New Orleans piano, ending at last with the most freakishly virtuosic of them all.

James Booker was a child prodigy who recorded his first hit at twelve and by fourteen was playing gigs under a fake i.d. In the course of his career, he was a sideman for Joe Tex, Aretha Franklin, Fats Domino, Ringo Starr, and Dr. John, with whom he remained friendly even after the bandleader fired him for erratic behavior.

You can get an idea of his musical range from the list of tracks on his 1976 studio album Junco Partner. Along with the title song, it includes an adaptation of Chopin’s "Minute Waltz," Leadbelly’s “Goodnight, Irene,” “The Sunny Side of the Street,” and “I’ll Be Seeing You.” Booker chose the last in imitation of Liberace, who always played it to close out his television show. He called himself the Black Liberace.

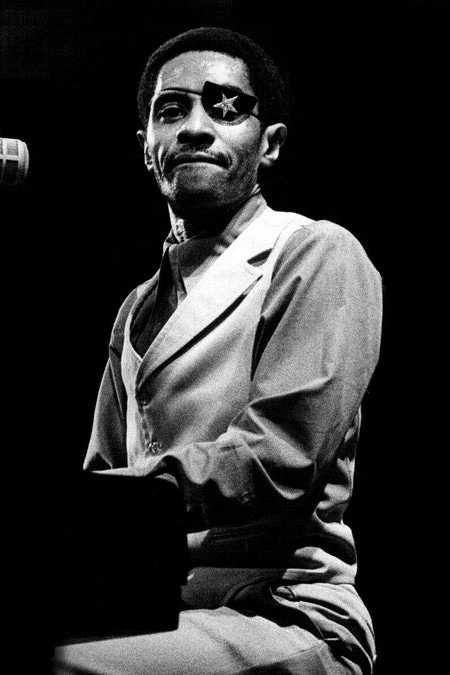

Booker was also the most colorful of the New Orleans triumvirate: one-eyed (he wore an eyepatch decorated with a sequined star), multiply addicted, and as resplendently queer as Liberace, though unlike Liberace, he made no pretense of being a heterosexual bachelor with a thing for candelabra. He once came onstage in a diaper, holding a gun to his head, and threatened to shoot himself on the spot if somebody didn’t give him some cocaine.

When you listen to Booker’s recording of “Junco Partner,” which is slower paced than the Doctor’s or the Professor’s, it often sounds as if two pianos were playing at once. George Winston said of him: “his little finger on his left hand is like the bass pedal on a Hammond [organ]. The top part of his hand is like a rhythm guitar or piano part. And his right hand is basically Aretha Franklin.” 6Booker's music is usually described as rhythm and blues and sometimes as jazz, but it also stands adjacent to ragtime, which from the moment of its appearance in the 1890s had a radical, transformative impact on American popular music. Ragtime was one of the first musics composed and performed by Black people to be widely adopted by white ones, even celebrated by them, as it was by Irving Berlin in his 1911 hit "Alexander's Ragtime Band."

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Peter Trachtenberg: Not Dark Yet to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.